In the excruciatingly long run-up to this remake of the beloved 1992 classic, the question on most of our minds was why it needed to exist. But this current glut of live-action Disney remakes has already proved its profitability many times over, and the question of why is easily counted in billions of dollar signs. The more interesting question to me is what this new version attempts to do, and whether it succeeds.

On a purely aesthetic level it’s a mediocre imitation of the animated version, with a nearly identical but less funny screenplay, cheap-looking CGI, and music that feels watered-down from the classic songs that are indelibly imprinted on any child of the nineties. The most obvious loss is of the mobile, lively, colorful charm that inevitably disappears in turning this story from a hand-drawn cartoon to a rather clumsy amalgamation of live action and visual effects. Iago, Abu and the magic carpet lack the personality and life that added so much to the humor and the world of the original film, and Will Smith’s Genie would have been fine, if we all had amnesia and forgot about Robin Williams—and there, too, CGI cannot in a million years mimic the elasticity, speed and humor of the animation that perfectly displayed Williams’ virtuosic performance. None of this is a surprise to anyone that’s been watching (and cringing at) the trailers.

This movie is not only trying, however, to recreate the magic of the original and play our nostalgia like Aladdin’s stolen lute. It also wants to “update” Aladdin from an Asian folktale appropriated and performed by white people in an Orientalist fantasy of an exotic “Arabian” kingdom. Disney is trying to erase the 1992 film’s problematic tropes to fit its new image as a corporation that wants to make stories for and about everyone.

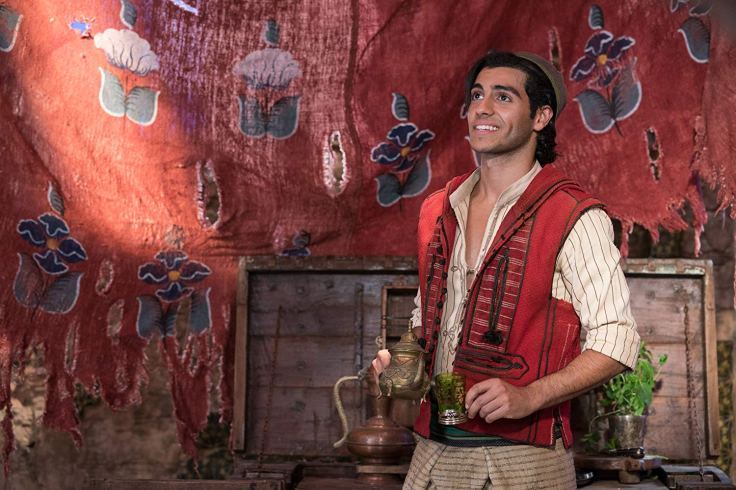

In some aspects, it even succeeds. The cast is mostly made up of people of color, even if the heroine is of biracial white and Indian ancestry. Mena Massoud is basically the cartoon version of Aladdin come to life, and he’s completely charming, as is Naomi Scott as a Jasmine with far more agency than her animated counterpart. (This movie also allows both of them more clothing, too, much closer to what people who live in a desert climate might actually wear.) Does it pass the Riz Test? Debatable, but I think it might just scrape by.

[some spoilers ahead, if that matters for a movie like this]

I was heartened, as well, to see that this version doesn’t put Jasmine in the disgusting position of being forced to romance and kiss Jafar, objectified and in chains. Her father is not forcing her to marry, although he refuses to give up on the long tradition of male rulers in their kingdom. (Nor does he, as in the 1992 version, simply offer the Sultanate to Aladdin.) Jasmine proves her father wrong and ‘earns’ the throne for herself, which in turn means she can decide to change the law that says she’s only allowed to marry a prince. These are important changes, because they challenge the tropes and imagery of the earlier film that made Jasmine an oppressed object of desire who exists only as a bargaining chip between the men around her, dressed in various belly-dancing costumes of the type that existed mostly in the imaginations of the Orientalists who first popularized the tale of Aladdin in Europe in the 18th century. You can see that the production team was at least trying to do better here.

Yet there are limits to how far an upgraded version of Aladdin can go under the leadership of a white male director and writers. Disney doesn’t seem to realize that this was also the biggest problem with the original version. Switching out the word “barbaric” in the opening song doesn’t erase the fact that we’re still seeing a vision of a fictionalized Eastern kingdom through the eyes of people who likely have no cultural context for Islamic or Arab cultures except for the hundreds of racist depictions that Hollywood has produced over the last century.

Mostly what I saw in this movie was a huge missed opportunity. A woman of color, an Arab and/or Muslim woman, should have been leading this team. People who know these cultures should have worked on the costume and production design. Instead we get an Agrabah that is a mishmash of Orientalist lite imagery that is trying to eat its cake and have it too; there’s real Arabic script on some documents and English on others, clothing that looks Moroccan and other dresses that look like they were made in India; a culture that sort of winks and nods at Islamic roots but is wiped of that identity in any real way.

For whatever faults the earlier film had, the characters were clearly Muslim: the Sultan used the exclamations “By Allah” and “Praise Allah.” This clear nod to Islam is one of the reasons that Muslim girls of my generation have such conflicted feelings about this movie—in some ways this was the first time we felt represented, and in such a well-made, fun, funny, beloved movie, but on the other hand, Jasmine was so clearly not us beyond her brown skin and her name. I certainly didn’t identify with her, because even as a young girl I saw how exoticized and objectified she was, even if I didn’t have the vocabulary to express it.

Aladdin 2019, if it had to be made, could have corrected these problems; more importantly, it could have been a milestone in Arab and Muslim representation the way that Black Panther was for the black community. That would have actually justified the movie’s existence. Instead, in the effort to avoid the Islamophobic tropes of the 1992 version, this one completely erases the subtle cultural influences of Islam that would exist in a place like this, and yet allows the filmmakers to slip away from the uncomfortable responsibility of authentic representation, because Agrabah is fictional.

This kind of reasoning not only lacks imagination, but more importantly, ignores the fact that a fictional land can still be very real in people’s minds: ask anyone who was moved to tears by seeing Wakanda represented onscreen last year. Or, even more pertinent to this movie’s wasted potential, witness the 30% of Republican voters who, when surveyed in 2015, said they supported bombing Agrabah (or the 54% who supported the Muslim Ban). I feel like a broken record at this point, but I’ll keep saying it until someone listens—these flattened, racist portrayals of Muslims have real consequences. Disney was more concerned with a milquetoast attempt at avoiding backlash than making history; more interested in a guaranteed bottom line than a new, smart, and interesting take that wouldn’t just fail to make us angry but would give us some joy. Perhaps even make us feel like our humanity was being recognized.

During the climactic fight with Jafar, when Aladdin outsmarts him by convincing that he’ll finally be all-powerful if he becomes a genie, the script changes the initial description of genies as the most powerful beings on earth to the most powerful beings in the universe; Genie is also referred to this way multiple times, all-powerful if not all-knowing. But no Muslim would ever refer to a jinn (a genie) as the most powerful being in the universe, because that’s Allah (God). And though this might seem like a small detail, it’s one of the most glaring ones to me, because it highlights how completely these scriptwriters have adopted only the barest of aesthetic tropes from a culture and religion that Hollywood has been exploiting since the silent era, playing on all the subtle Islamophobic cues that have built up in the minds of the audience in order to engender the reactions they want, without having the decency to respect the fundamental beliefs of billions of people that are actually not all that difficult to research. Yet given who made this movie, it’s unsurprising: when you don’t come from a culture, you don’t even know what you’re being ignorant about, so you can’t fix the problem.

Another example of this is the mixture of Arab and South Asian costumes and influences; many others have pointed out the Bollywood-style dance at the end as out-of-place and perplexing. The writers could have easily remedied this by explaining that Jasmine’s mother was from a fictional land in South Asia, which would have been an easy fix to the confusion of Naomi Scott’s casting, and would have made the cultural blending look purposeful and interesting (and even historically accurate—after all, there was lots of migration and intermarriage between different ethnicities in the Islamic empires) rather than confused and poorly researched. Jasmine’s dupattas could have seemed like an homage to her dead mother; Raja’s name, which means “prince” in Urdu/Hindi, a nod to her mixed heritage. An authenticity of details could have elevated this film beyond simply a near-identical do-over with worse animation and better gender politics.

It was nice to see a cast with actors of color playing these characters who, whatever I might feel about them now, were part of a beloved movie that I watched over and over as a child. But what this movie mostly showed me is that once again, Hollywood really doesn’t care about representing Muslims and Arabs with respect, and doesn’t feel the need to put us behind the camera in any real capacity. So even though I love our new Aladdin and Jasmine, they really deserved better from this movie—and so did we.

Thanks for the good and informative read, Anisa.

I came across it from a post you linked to on Dramabeans

*squealing at “finding” a fellow Beanie in a different context*

What I truly praise BLACK PANTHER for is highlighting African people with heavy accents on their tongue as exactly what we are: perfectly intelligent people, who don’t need subtitles to be understood by the average White person. I haven’t watched the new ALADDIN; how did you feel about the use (or therein lack of) of accents in dialogues?

The other interesting thing about Black Panther for most Black folks (African American and African alike — the distinction is intentional) is that it really WAS a melting pot type of movie for Black Culture at large. Wakanda itself draws from soooo many countries on the Continent. almost too many. But a movie directed by an African American man was bound to have a better lens on Afro-centricity in a movie, than another person. BLACK PANTHER was clearly written and directed with the intent of celebrating every glorious aspect of Black culture.

*cough* and it “stole” a LOOOOT from THE LION KING, but hey *cough*

Maybe, as you pointed out, that is what was missing from ALADDIN? Not just thorough research but more purpose? Was the intent of the movie to simply be a more politically correct reboot of the original animated movie, or was it supposed to be a celebration of the Muslim culture at large?

I’d like your take on this, if you have time.

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kethy! Thanks so much for reading. ALADDIN’s main cast all speak with American accents, which is another function of the way the movie exists in a sort of Orientalist neverland – BLACK PANTHER, on the other hand, may be fictional but it very much exists in the real world, which is shown in the authentic and respectful pan-African influences and its nuanced discussion of issues faced by both Africans and African Americans. (And LION KING is based on Hamlet, which is based on the story of the African King Negus, so I think the “stealing” ship sailed long ago, haha.)

As I said in the review, there was neither the intent nor the effort to celebrate Muslim culture in any way – just a cash grab of a movie that got rid of the most glaringly problematic stuff in the 1992 version but didn’t bother to actually remake it in a way that would justify the movie’s existence.

LikeLike